Ancient Maya blessed their ballcourts

For sports fans, places like Fenway Park, Wembley Stadium or Wimbledon's Centre Court are practically hallowed ground.

Archaeologists at the University of Cincinnati found evidence of similar reverence at ballcourts built by the ancient Maya in Mexico.

Using environmental DNA analysis, researchers identified a collection of plants used in ceremonial rituals in the ancient Maya city of Yaxnohcah. The plants, known for their religious associations and medicinal properties, were discovered beneath a plaza floor upon which a ballcourt was built.

Researchers said the ancient Maya likely made a ceremonial offering during the ballcourt’s construction.

“When they erected a new building, they asked the goodwill of the gods to protect the people inhabiting it,” UC Professor David Lentz said. “Some people call it an ‘ensouling ritual,’ to get a blessing from and appease the gods.”

The study was published in the journal PLOS One.

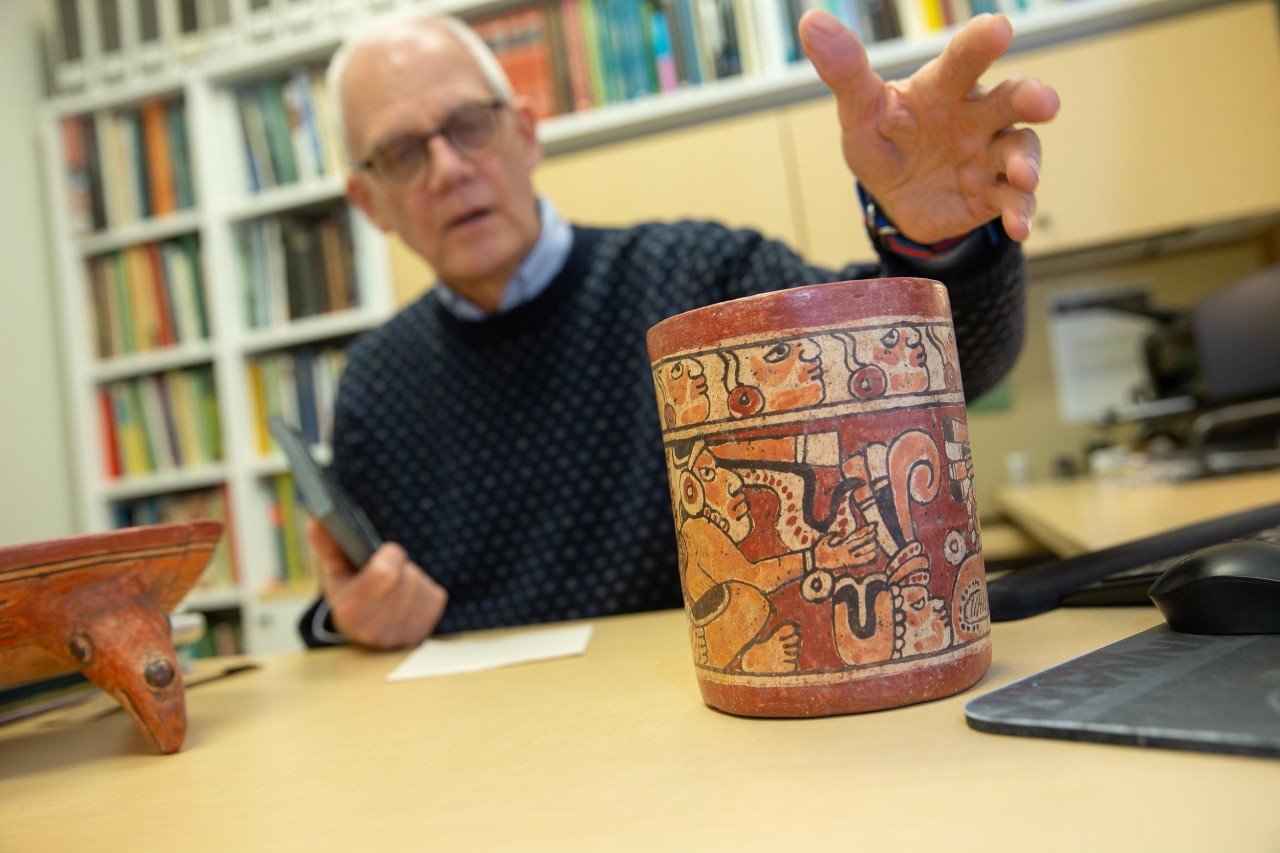

UC Professor David Lentz holds up a sculpture that bears reproductions of ancient Maya glyphs. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

The research was carried out through Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History in collaboration with researchers from the University of Calgary, the Autonomous University of Campeche and the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Lentz and his research partners have been studying ancient Mesoamerican cultures across Mexico and Central America. New tools that can identify environmental DNA are helping them unlock secrets about how the ancient Maya might have used these spaces.

Researchers from 2016 to 2022 worked at Yaxnohcah in Campeche about 9 miles north of the border of Guatemala, where they excavated a small area of a ballcourt.

The ancient Maya played several ball games, including pok-a-tok, which was a mix of soccer and basketball. Players tried to get a ball through a ring or hoop on a wall.

“But not all of the ballcourts had hoops,” Lentz said. “We think of ballcourts today as a place of entertainment. It wasn’t that way for the ancient Maya.”

Ballcourts occupied prime real estate in the ceremonial center. They were a fundamental part of the city.

David Lentz, UC College of Arts and Sciences

He referenced a famous Mayan myth of hero twins who must play a ballgame with the gods to escape the underworld. And researchers believe in some instances, competitors were sacrificed at the conclusion of the match.

In some ancient Maya cities like Tikal in Guatemala, ballcourts were built prominently next to the biggest temples.

“Ballcourts occupied prime real estate in the ceremonial center,” Lentz said. “They were a fundamental part of the city.”

Many construction projects today are subject to ceremony, from groundbreaking to the placement of the last steel beam to the ribbon-cutting. The ancient Maya, too, were deliberate about their construction ceremonies as well.

“The nearest analogy today might be like christening a new ship,” Lentz said.

UC Professor David Lentz and his research partners used environmental DNA to identify evidence of plants of ceremonial significance buried beneath an ancient Maya ballcourt in Mexico. Here he talks about a reproduction ceramic chocolate mixer featuring ancient Maya iconography. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

UC Professor Emeritus Nicholas Dunning collected a sample of sediment at the base of a sidewall. Here, in a place known as the Helena complex, researchers believe stood a civic ceremonial platform consisting of 1-meter-high stone and earth.

The site started out as a humble residential structure built on bedrock, Dunning said. These community founder sites grew into places enshrined by monumental architecture, he said.

“Over time, important family members were buried within the expanding platforms, imbuing these places with power. The Maya practiced ancestor worship,” Dunning said.

“In a sense, structures like the Helena Group were thought to be alive or to have souls that needed to be nourished,” he said.

Dunning said when buildings were expanded or repurposed, as with the ballcourt, the ancient Maya made offerings to bless the site. Archaeologists sometimes find ceramics or jewelry in these offerings along with plants of cultural significance.

“We have known for years from ethnohistorical sources that the Maya also used perishable materials in these offerings, but it is almost impossible to find them archaeologically, which is what makes this discovery using eDNA so extraordinary,” Dunning said.

A decorative ring made from carved stone is embedded in the wall of a ballcourt in the ancient Maya city of Chichen Itza. Photo/LanaCanada

Ancient plant remains are rarely discovered in tropical climates, where they decompose quickly. But using environmental DNA, researchers were able to identify several types known for their ritual significance.

“Ancient DNA sequencing is amazing,” said Alison Weiss, a study co-author and professor emerita with the UC College of Medicine.

UC researchers used a product called RNAlater to preserve the samples during transit back to the labs. Special probes that are sensitive to species found in that region helped them single out the fragmented DNA of several species, she said.

They discovered evidence of plants associated with ancient Maya medicine used in divination rituals.

A type of morning glory called xtabentun is known for its hallucinogenic properties. Today, people brew mead from the honey of bees that feed on the pollen of xtabentun flowers.

Chili peppers today are a favorite spice around the world. But for the ancient Maya, chili peppers were used to treat a variety of illnesses. An offering of chili peppers might have been intended to ward off disease, Lentz said.

“We think of chili as a spice. But it was much more than that for the ancient Maya,” Lentz said. “It was a healing plant used in many ceremonies.”

Researchers also identified the tree Hampea trilobata or jool. The leaves of this tree were used to wrap food bundles for Maya ceremonies. The ancient Maya also wove food baskets from twine made from the tree’s bark. And it was used in medicines to treat snake bites.

Lastly, researchers found evidence of the plant lancewood or Oxandra lanceolata. Its oily leaves are a known vasodilator, anesthetic and antibiotic agent.

I think the fact that these four plants, which have a known cultural importance to the Maya, were found in a concentrated sample tells us it was an intentional and purposeful collection under this platform.

Eric Tepe, UC College of Arts and Sciences

Botanist and UC Associate Professor Eric Tepe said finding evidence of these plants together in the same tiny sediment sample is telling. He has studied modern plants in the same forests once traveled by the ancient Maya.

“I think the fact that these four plants, which have a known cultural importance to the Maya, were found in a concentrated sample tells us it was an intentional and purposeful collection under this platform,” Tepe said.

Researchers for years have identified the diets and uses of plants among ancient cultures by studying trapped pollen, preserved charcoal and ancient refuse piles. Now environmental DNA holds the promise of helping researchers learn even more about ancient civilizations, Tepe said.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if this tool becomes more common. You gain insights you wouldn’t learn any other way,” he said.

Researchers noted the challenge of trying to interpret a collection of plants through the opaque lens of 2,000 years of prehistory. But Lentz said the findings help add to the story of this sophisticated culture.

Researchers believe the ancient Maya devised water filtration systems and employed conservation-minded forestry practices. But they were helpless against yearslong droughts and also are believed to have deforested vast tracts for agriculture.

“We see the yin and yang of human existence in the ancient Maya,” Lentz said. “To me that’s why they’re so fascinating.”

Featured image at top: A painting on a serving vessel depicts ancient Maya in costume playing a game with a ball. Photo/Dallas Museum of Art

UC Professor David Lentz has studied ancient civilizations across North and South America. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation and impact. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Latest UC News

- Cincinnati Enquirer: UC students win Flying Pig racesUniversity of Cincinnati students won championships in the 2024 Flying Pig Marathon, including the women's marathon and men's and women's half marathons, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported.

- Lindner alumnus Xander Wells named Mr. BearcatXander Wells approached his college experience with the idea that he’d rather depart the University of Cincinnati wishing he had done less than wishing he had done more. Mission accomplished for the recipient of the 2024 Mr. Bearcat award, as selected by UC honorary fraternity Sigma Sigma.

- Donate instruments at LINKS drive on May 10-11Through the Lonely Instruments for Needy Kids (LINKS) program, you can donate your used band or orchestra instrument to a young musician who cannot afford to rent or purchase their own. The LINKS instrument donation drive is at 10 a.m.-4 p.m. this Friday, May 10, and Saturday, May 11 2024, at any Willis Music or Buddy Rogers Music location. A project of CCMpower in partnership with Willis Music and Buddy Roger’s Music, LINKS began in 1994 as the brainchild of CCM alumnus Bill Harvey (BM Music Education, 1971). The owner of Buddy Roger’s Music, Harvey wanted to fill the need for students whose parents were unable to buy, rent or borrow an instrument. The solution was to create a “recycling program” for musical instruments.

- CCM alumnus wins 2024 Solti Conducting AwardUC College-Conservatory of Music alumnus François López-Ferrer (BM Composition, ‘12) is the recipient of the prestigious Sir Georg Solti Conducting Award, awarded annually to a promising American conductor 36 years of age or younger. One of the largest of its kind, it provides essential career guidance, industry connections and a cash award of $30,000 to aid grant recipients as they further hone the skills of their craft.

- Washington Post: The hour after leaving day care is a nutritional fail for kidsThe Washington Post highlighted research led by University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children's Hospital researchers that found kids eat fewer healthy foods and take in 22 percent of their day’s added sugar intake in the single hour after they’re picked up from child care.

- Local news highlights UC's artificial intelligence programsUC College of Engineering and Applied Science Professor Ali Minai tells WLWT and WVXU that AI is becoming a popular subject among new students.